How many photographs have you taken in your life? Or even just today? It’s remarkable to realize that 150 years ago, it would have been extraordinary to have more than one photograph taken of yourself!

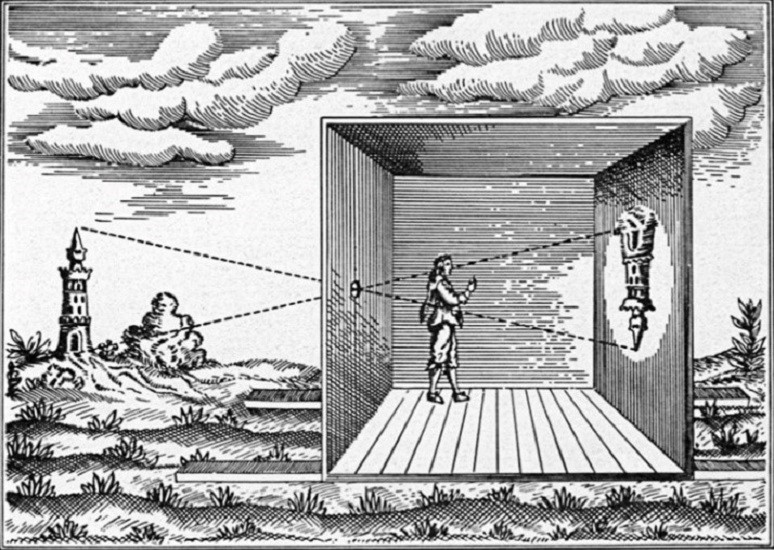

Photography started many centuries ago with the invention of the first cameras, which were used for drawing — not for taking pictures.

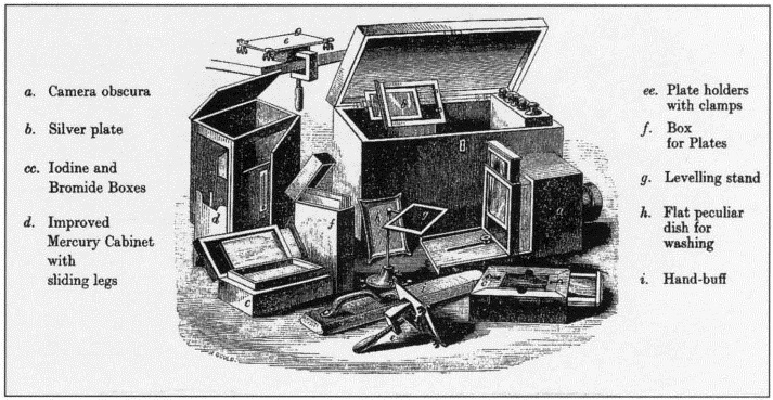

The first camera was the camera obscura, which means “dark room”.

It was officially invented 700 to 800 years ago! A camera obscura is a darkened room or box, fixed with a small opening to allow in light.

An image would appear upside-down on the opposite surface. People used this technique to draw life around them!

You can make your own camera obscura with a cardboard box and a few other ordinary household items.

DISCOVERY

During the late 18th century the rising middle class wanted “cheap” portraits. Scientists worked to figure out how to make light itself fix the image in the camera without having to draw by hand.

In 1839 a discovery was made! A French artist named Louis Daguerre figured out that by placing a thin sheet of metal coated in certain chemicals inside a camera obscura, he could capture an image as the chemical-coated metal reacted to the light entering the camera.

DID YOU KNOW? The word photography means “writing with light”!

Louis Daguerre presented his discovery of photography as “a chemic and physical process which gives nature the ability to reproduce itself”.

Others also experimented with ways to take photographs. The biggest problem was keeping the picture from fading away.

Through trial and error, scientists discovered a better way to take pictures of people, using paper! One advantage of this new process was that people didn’t have to stand still for so long when having their pictures taken.

As the technology advanced, it became increasingly popular to give photographs to friends and family. People finally could see what they looked like more accurately than in a drawing or painting!

Photography began as a curiosity, but as its pioneers found innovative new ways to capture light and reproduce images, it changed fundamentally the way we interact with the world around us.

Let’s take a closer look at three different kinds of 19th century photographic innovations.

Daguerreotype: Mirror with a Memory

Select image to view full-sized.

Each picture is a unique, mirror-like image on a silvered copper plate.

Daguerreotypes were produced and sold in folding cases because of their fragile nature.

Daguerreotypes were always meant to be handheld, because the image could only be seen from a specific angle.

Subjects often looked serious in early daguerreotypes, because it took several minutes of sitting still to capture an image!

It was an expensive process to make these “portable portraits”, and they were accessible only to people who could afford them.

ACTIVITY: THE DAGUERROTYPE CHALLENGE! How long can you sit still and hold a smile? When sitting for a daguerreotype, any movement could result in a blurry photograph. Challenge your family to a “daguerreotype challenge”: Have each person choose a pose or facial expression that they think they can hold. The person who stays absolutely still the longest wins!

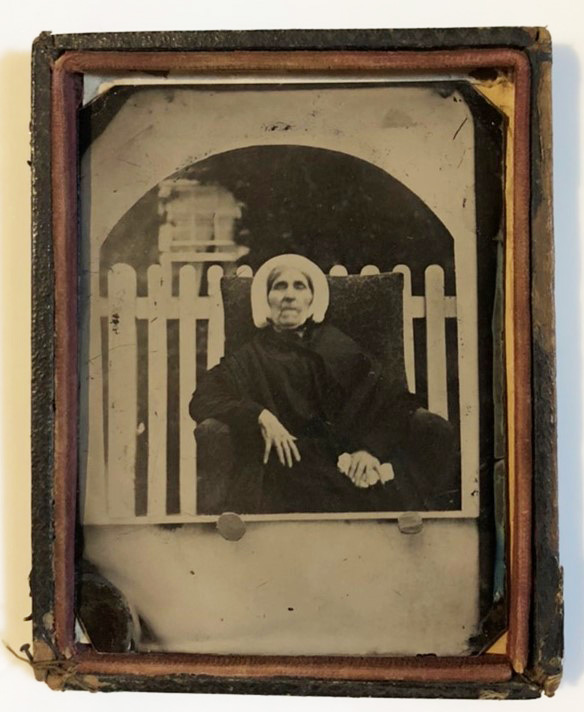

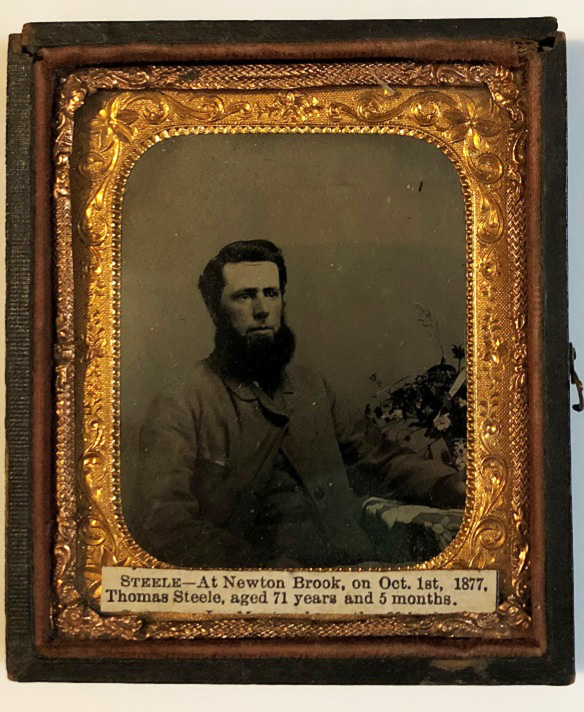

Tintype: Accessible Photographs

Select images to view full-sized.

The tintype process produced an underexposed negative image on a thin iron plate, which was then blackened by paint or enamel and covered in emulsion.

This method was a quick and inexpensive. Tintypes, unlike other photographs at the time, did not need to be mounted in cases, so photographers could prepare, expose, develop, and lacquer a tintype plate within minutes for customers!

DID YOU KNOW? Tintypes were made from iron, not tin. They were named for their “tinny” feel!

QUESTION: How would you feel if you knew this might be the only photo you ever had taken?

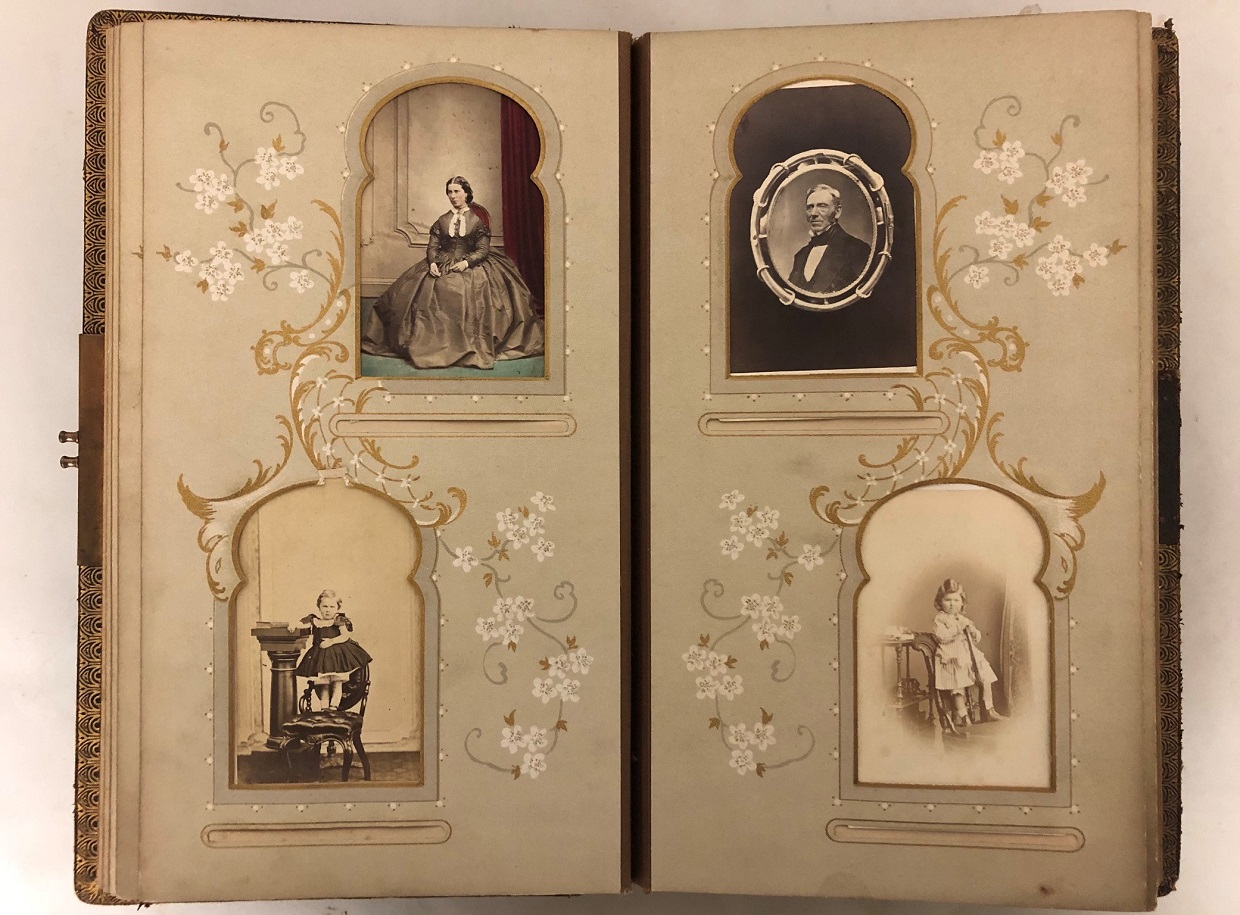

Carte-de-visite: The Original Calling Card

Select images to view full-sized.

The use of paper allowed for multiple copies to be made at one time, so that people could hand them out to loved ones and friends.

This made the carte-de-visite the most popular type of photography in the 19th Century.

Where do we take photos today? Everywhere! But in the 1860s you had to visit a photography studio if you wanted your picture taken. It wasn’t until later in the century that further innovations and more affordable equipment made it possible for amateur photographers to take photographs at home.

|

Since these first early photographs were taken, we have produced more than 3.5 trillion photographs. Another 1.4 trillion will be taken this year alone!

With cameras on our phones, our computers, and even our doorbells, photography is now ingrained in everyday life. It is incredible to think that it all began with a tiny pinprick of light in a box.